Full Circle

Nearly 250 years after it was intercepted by the British, this Dunlap broadside is returning to Philadelphia

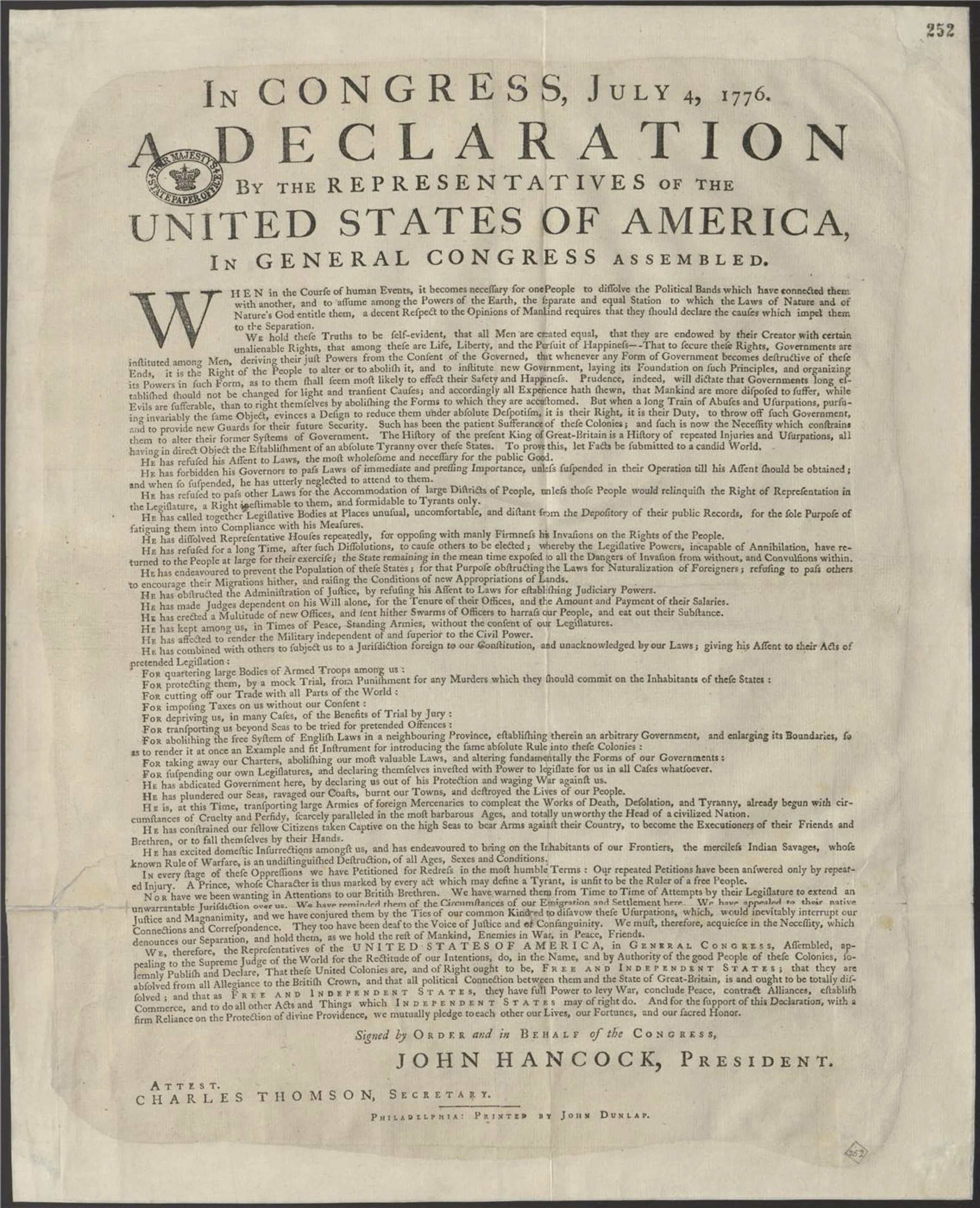

On a summer day in Kew in 2016, I flipped through the pages of intercepted correspondence from the Revolutionary War. There was a letter from Joseph Wilcocks in Philadelphia to two merchants in London. A bill of exchange from Willing, Morris and Company. A hasty message to Edmund Randolph from his uncle. A list of products that Jonas Phillips wanted to sell in his Philadelphia store. A lengthy—and messy—letter written in Charleston, South Carolina, recounting the British defeat at Sullivan’s Island. Tucked in between them was a piece of paper, printed off by the National Archives staff in 2009 to replace one of John Dunlap’s broadsides of the Declaration of Independence, which the staff had decided to store in an external folder.

It wasn’t until years later, while doing research for the Museum of the American Revolution’s exhibition, The Declaration’s Journey, that I realized the connection between some of these intercepted documents. The bill, the list of goods, and the Declaration of Independence had something in common.

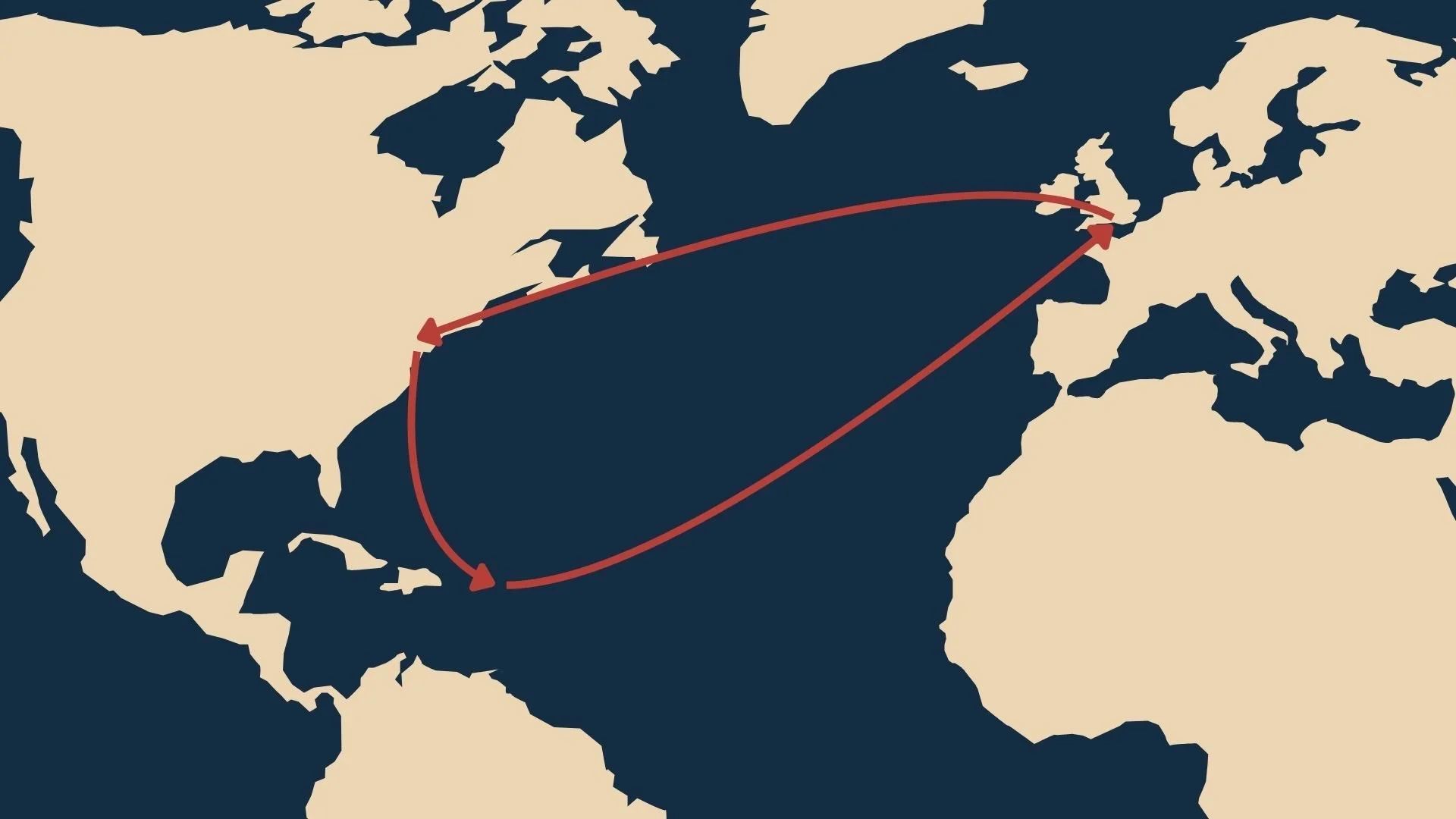

These three documents were all folded up and enclosed by a cover sheet. Anyone who has made a paper football knows how folding paper again and again creates a tight bundle. The Dunlap broadside of the Declaration of Independence would have been folded in half vertically, and then folded over horizontally to fit inside the cover; some of these fold lines are still visible. It would have nestled in with the bill of exchange and list of goods—smaller pieces of paper that were easier to fold. The cover sheet was addressed to Amsterdam by way of the Dutch Caribbean island of Sint Eustatius. On the other side of the address, a merchant on Sint Eustatius named Samuel Curson added a note, indicating that he had received this small package on September 24, 1776 and forwarded it to Amsterdam.

Sometime after it left Sint Eustatius, this package fell into British hands. The enclosed documents have been in the intercepted papers at the National Archives ever since.

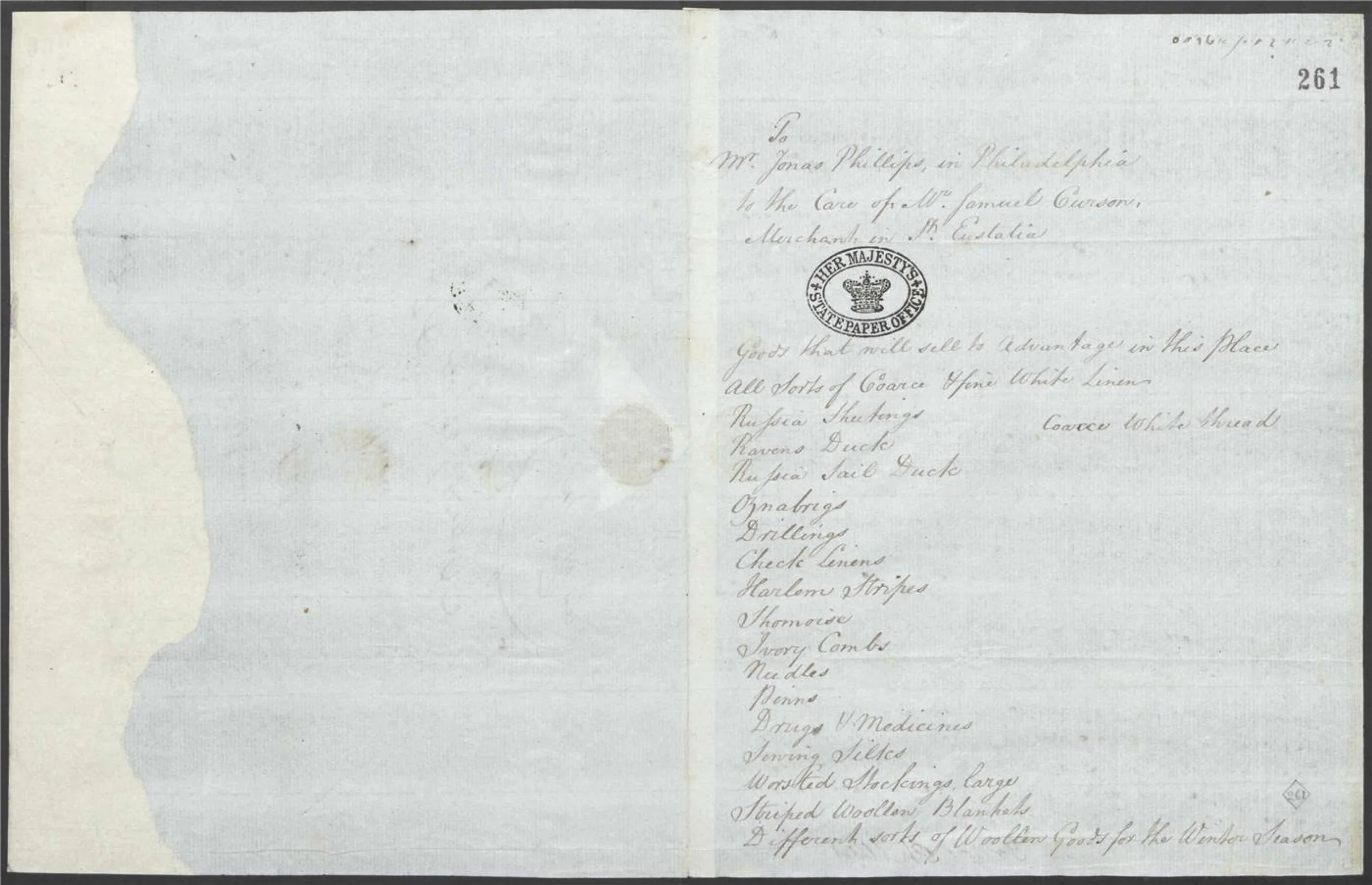

The intercepted papers were numbered in the upper right hand corner of each document. Every page was also marked with a stamp reading “HER MAJESTY’S STATE PAPER OFFICE.” The bill of exchange was stamped 251. The Dunlap broadside of the Declaration of Independence was stamped 252. The cover sheet was stamped 260. And the list of goods that Jonas Phillips wanted to sell was stamped 261.

Although the order of these documents became shuffled in the archives, it is clear that they all tie back to Phillips. He was the one who sent the Declaration to Gumpel Samson, a merchant in Amsterdam who was part of Phillips’s extended family. Or, at least Phillips tried to send the Declaration.

On the other side of the list of goods that he wanted to sell in his Philadelphia store, Jonas Phillips wrote a letter in Judeo-German, or Yiddish, which connects these documents together. Phillips shared the Declaration of Independence because it was the latest news in Philadelphia. He enclosed the bill of exchange because he wanted to send money to his mother, who was living in Europe, perhaps in the German state of Hesse, where Phillips was born.

Jonas Phillips’s Dunlap broadside is special on multiple counts. It helps to tell the story of the growing Jewish American community in Philadelphia at the founding of the United States. It is the most recently identified Dunlap broadside. And, nearly 250 years after it was intercepted by the British, this Dunlap broadside is returning to Philadelphia, along with Phillips’s letter in Yiddish with his first impressions of independence.

There will be much more about Jonas Phillips’s Dunlap broadside in my forthcoming book, When the Declaration of Independence Was News, and the Museum of the American Revolution’s special exhibition, The Declaration’s Journey. In the meantime, check out this video:

Where to See It In Person: The Declaration’s Journey, Museum of the American Revolution, October 2025–January 2027